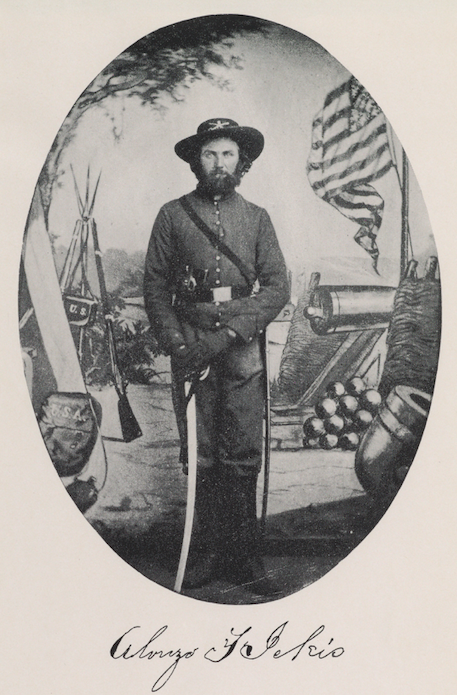

Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis was the first person I wrote about in The Three-Cornered War.

I found his wartime diary in the Western History Collection at the Denver Public Library during my initial research trip for this project, in 2010. It is a small, leather-bound volume, and Ickis wrote over his initial penciled descriptions in ink. This suggested revisions, an interplay between the past and some point later in the past.

But as I read through the daily entries, which detailed Ickis’ service in the Union Army in Colorado and New Mexico between October 1861 and November 1862, I realized that although Ickis clearly had the opportunity to change his words and therefore craft a more, well, respectable perception of himself, it did not appear that he had.

Ickis described the drunken carousing, the dancing, and the pranking that predominated in Union Army camps in the mountains. He used racial epithets to describe Hispanos serving in the Army with him. He freely expressed his racism, his love for his fellow soldiers, and his fear and then elation in the face of battle. He was, in short, a pretty perfect source.

Alonzo Ickis had come to the Rocky Mountains in the spring of 1859, part of a stream of migrants—most of them white, Midwestern, and male—looking to make their fortunes during the Colorado Gold Rush. He and his older brother Johnathan made the more than 600-mile journey from their farm in Iowa to Denver City, and then went up into the diggings.

They had no luck in the mines but kept trying, and supplemented their meager incomes by buying and selling items that other miners needed, and lending them money. The latter business led Ickis to buy a gun, and learn how to use it.

When he enlisted in the Union Army in October 1861, he did so with more than ninety other miners, most of whom he knew. He was animated by a sense of obligation, writing to his family in Iowa that, “I do think it is the duty of every single man to enlist and do all in his power to end this war.”

Readers of The Three-Cornered War will follow Ickis as he trains for battle in army camps in Colorado, marches to Santa Fe through winter snowstorms, and then continues down the el camino real de tierra adentro to fight Confederate Texans at Valverde in central New Mexico. Ickis remained in New Mexico until November 1862, when Brig. Gen. James Carleton kicked his company out of the Santa Fe and sent them back to Colorado as punishment for their bad behavior.

I can’t quite believe that it has been almost 10 years since I first “met” Alonzo Ickis in the quiet of the reading room at the Western History Collection. His was a vivid voice from the start. His diary revealed to me what soldiers’ lives were like on the ground, and the many ways that gold mining was inextricably linked to the Civil War in the far West.

***

In order to tell Ickis’ story, I used his diary at DPL and the letters and biographical information collected in Nolie Mumey’s Bloody Trails along the Rio Grande (1953); the accounts of other miners serving in the Union Army, especially the eloquent Ovando Hollister (Boldly They Rode); battle reports collected in the OR; histories of mining in Colorado; and Elliott West’s classic environmental and western history, Contested Plains (1998).

Do you know where in Iowa Ickis had lived? Had he farmed there or been otherwise engaged? (Am still reading your book, so apologies if this info is mentioned further on.)

Any idea when/where that photo of Ickis was taken? The backdrop looks identical to one in a photo in the Library of Congress of a USCT soldier at Benton Barracks, Missouri in 1864: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.36456/

Not sure how common it was for photographers to have stock backdrops, but, if it is the same, that would suggest Ickis had the photo taken sometime during the winter of 1863-64 when the Second Colorado was also at Benton Barracks, and after it converted from infantry to the cavalry arm (evidenced by the pistol he is wearing and the saber he is holding, as well as the crossed saber insignia on his hat).

Yes, you are correct! A historian of photography identified that backdrop for me a while back, as one in common use among photographers in the St. Louis area in 1863-64, so the Benton Barracks connection would make sense!