A tall figure strides toward you through the fog. Then you see him from the back as he walks up a hillside, dragging his left hand through the tall grass. There he is again, staring out at the Pacific Ocean. Always in a long black coat and a stovepipe hat, a hint of a beard evident when he turns his head to the side. Yep, it’s him. Abraham Lincoln. Contemplative. Commanding. Hawking the 2013 Lincoln MKZ on television.

This is not Abe’s only commercial. In recent years, he has sold Geico insurance, Diet Mountain Dew, and Quicken Loans, among other products. He seems to be everywhere, in commercials but also television docudramas, online videos, several episodes of Drunk History, and major motion pictures. However, these versions of the nation’s 16th president are only partially recognizable to those who study nineteenth-century American history. They make use of historical details (That beard! That hat! The Gettysburg Address!) but they tell us more about the nature of popular media—and its fortes, parody and satire—than about the past. There are two Lincolns that currently dominate popular media.

Bromantic Partner

In the films, especially, the central relationship is not between Lincoln and Mary Todd, or Lincoln and his sons, or even Lincoln and his political adversaries. It is a bromance, in some form or another. This friendship takes precedence over all other relationships in Lincoln’s life, and in films, it drives the plot. In Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, a young Abe spends the first part of the film in the shabbily genteel home of Henry Sturges, who has saved Lincoln from certain death at the hands (or rather, fangs) of a slave-trading vampire.

Henry subsequently trains him to hunt and kill vampires using, of course, an axe. Cue the scenes of male bonding, as Henry bloodies Lincoln up in order to teach him to defend himself. In addition, one of the major plot points of the film—Joshua Speed’s betrayal of Lincoln to his vampire enemies—hinges on our recognition of Speed’s jealousy of Lincoln’s relationships with Mary Todd and Will Johnson. Later in the film, as President Lincoln, Speed, and Johnson plan strategy in his White House office, Mary appears in the doorway and asks, “May I have my husband back?” Yeah. Good luck with that.

Even the brief Cartoon Network short “Batman and Abe Lincoln vs. John Wilkes Booth” is a bromance of sorts. In a reimagined night at Ford’s Theater, Batman swoops in to save the president from the steam-powered cyborg John Wilkes Booth. When Abe asks, “Who are you?” Batman replies, “Just a long-time admirer.” Then they work together to bring Booth down.

The bromantic Lincoln is compelling; you want to hang out with this Abe, kick back in the kitchen with him like Thaddeus Stevens does in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, the lucky bastard. This president is smart, amusing, and fun to be around. And although most of these media depictions complete revise history—or portray an alternate universe—they all bring us into Lincoln’s world, and into an imagined relationship with him. Which is, of course, what much of popular media is intended to do.

Action Hero

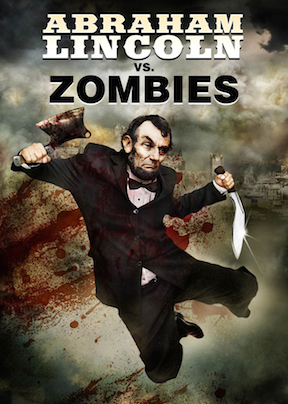

And this is why the simultaneous trend in depicting Lincoln as an action hero—and particularly, a hero who fights supernatural enemies—is so fascinating. The writers and directors behind Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, “Batman and Abe Lincoln,” Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies, and the YouTube trailer “Abraham Lincoln: Alien Puncher” have all taken this American icon and turned him to other uses, reimagining his life and presidency—and American slavery—along the way.

These action films take the viewer back to Lincoln’s life before he was president, or even contemplating political leadership. And they suggest that the central components of Lincoln’s career can be explained by his entanglements with supernatural beings.

Vampire Hunter, for example, reimagines the death of Lincoln’s mother as a murder by vampire. Zombies, in turn, positions Nancy Lincoln’s demise as part of a widespread zombie epidemic. In each of these films, this traumatic experience drives the young Lincoln to develop his abilities to kill the undead in order to exact his revenge. In “Alien Puncher,” a young Lincoln—“just a simple boy fixin’ to go to law school”—stumbles upon a time machine in the woods and transports himself to a future in which alien robots have taken over Earth. He helps the survivors defeat the robots, and then returns home to the 1830s.

Each of these Lincolns uses pre-industrial technologies—an axe, a scythe, and brass knuckles made from the Liberty Bell, respectively—to defeat his enemies. He is able to wield these weapons so effectively because of his superior athleticism. Decades spent in law offices and in Congress have clearly not diminished his physical prowess. When Batman directs Lincoln to “aim for that valve” to deactivate Booth’s cyborg suit, Lincoln throws his axe with spot-on accuracy. Booth explodes. In all of these depictions Lincoln’s action hero status is signaled by slow motion, special effects, and dramatic music that accompany his killing sprees.

In reimagining Lincoln as an action hero, these films also rewrite Civil War history, and the history of slavery. Vampire Hunter, for example, explains slavery as an elaborate system developed to feed Southern (white) vampires and prevent them from rising up against the federal government; this arrangement has been the key to holding the Union together. The vampire leader Adam justifies this perpetuation of slavery by saying, “Men have enslaved each other since they invented gods to forgive them for doing it.” This rhetoric merges with the discourse of the rights of man when Adam urges Lincoln to kill Henry: “Break your chains. Kill your master. Be free.” When the war breaks out, Jefferson Davis goes to meet with Adam, to recruit vampires to the Confederate cause. “If we support you,” Davis says (apparently referring to the Confederacy’s insistence on the legalization and expansion of slavery), “you will need to support us.” The vampires go to war dressed in gray, and this (the film contends) explains the Confederacy’s victories through early 1863.

The South’s slaves get their revenge, however; they are the ones who deliver all of the North’s silver to the battlefield outside Gettysburg, where the vampires are defeated and the tide of the war turns.

In “Alien Puncher,” Lincoln interprets the defeat of humans by the alien robots as a form of slavery. “We gotta destroy [them],” he tells the lone robot-invasion survivor. “Slavery just ain’t right.” And in the seconds before he launches himself skyward to punch the alien robot mother ship into submission, Lincoln looks at the camera and says, “Emancipation … Proclamation!” It is Lincoln’s experience with the enslavement of the entire human race in the future that shapes his policies in the past. In the short film’s final scene, the survivor says to Lincoln, “Remember what you said about slavery? … Remember that when you get back.” Lincoln looks confused, then says, “Ooooh! The slaves! Good call.”

In re-imagining slavery in these ways, these films erase Lincoln’s own evolving beliefs about slavery and emancipation; slavery is a national monstrosity that Lincoln has recognized as morally wrong since his boyhood. For viewers, these reformulations of slavery are less threatening than history books or a film like 12 Years a Slave because they allow us to avoid reckoning with the violent realities of the slave system; instead, they invite us to laugh (in a kind of astonished way) at the ludicrousness of these depictions.

And there is also amusement to be found in the contrast between the serious, careworn Lincoln—wrinkles like deep crevasses, the somber expressions—and the vigorous, badass Lincoln striding through cities and forests, dispatching vampires, cyborgs, and zombies with brutal efficiency.

So: why Lincoln? First, Lincoln is the most visually recognizable of all American presidents, challenged only by George Washington (who is becoming increasingly popular of late, with his own star turns in commercials and in the Fox television show Sleepy Hollow). His physical features and dimensions delighted political cartoonists in the 1850 and 1860s, and are still compelling to satirists today.

Second, his status as the most revered American president not only invites parody but ensures that revisions of Lincoln will not fundamentally undermine his legacy. Because the makers of these films and commercials have not smashed the pedestal to pieces; Abraham Lincoln continues to be an object of devotion in these new forms. We love him still—perhaps even more—when we watch him leap into the air in slow motion, swinging his deadly axe.

Enjoyed your analysis! In art, too, Lincoln seems to be everywhere, from fine art to commercial illustration to kitsch. Ever seen Lincoln as hipster or in a portrait made from pancakes? We’ve collected a few recent images and posted them here: http://www.pinterest.com/loyaltyofdogs/lincoln-as-some-people-imagine-him/

Lincoln seems modern to young people, one reason he can function outside of time.

My favorite is still the Geico commercial. Love the Abe.