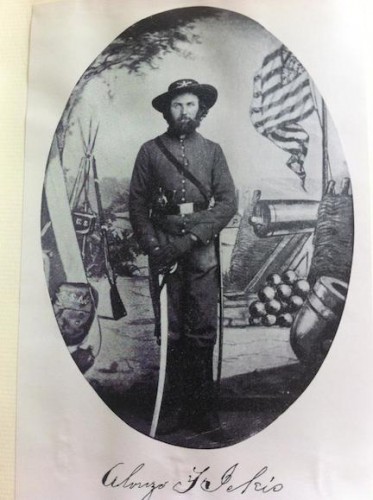

On a chilly day in December 1861, an Iowa farmer and Colorado gold miner named Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis put on his Union uniform—what he called his “suit of Sam’s best”—and set out from Cañon City with ninety fellow soldiers in Company B, 2nd Colorado Infantry. Their destination was Fort Garland, a federal installation built in 1858 to protect American traders and emigrants traveling through the San Luis Valley. There they would muster into the Union Army, and then move on to Santa Fe. It was not the ideal time to be marching through the Rockies; winter had set in, and the snows in the mountains were deep.

Their route was an eighteenth-century trapper’s path known as the “Taos Trail.” The road wound its way from the Arkansas River down the Huerfano, and then cut to the southwest, up over the Sangre de Cristo Pass and down the San Luis Valley and into New Mexico Territory.

On September 5, 2014, I put on my driving clothes (jeans, t-shirt, hoodie) and set out by myself for the daylong drive from suburban Denver to Santa Fe. The conditions were less than ideal—foggy, spitting rain, with temperatures falling to 40 degrees over Monument Pass into Colorado Springs. But unlike Ickis–who had to pull wagons up and over the icy slopes of Sangre de Cristo Pass—I had satellite radio and a seat warmer.

My drive to Santa Fe on that day could not possibly approximate Ickis’ experience on the march to war in the winter of 1861-62; I was not out to get a “period rush” from being where he and his company had been more than 150 years before. Rather, I wanted to follow his route through southern Colorado and northern New Mexico because, as an environmental historian, I believe that understanding the topography, hydrology, climate, flora, and fauna of particular places helps us to understand the ways that humans behave in those places—and vice versa. And in this particular case, tracking Alonzo would illuminate not only his own wartime experience but also the ways that this region was a particularly challenging theater of war for American soldiers.

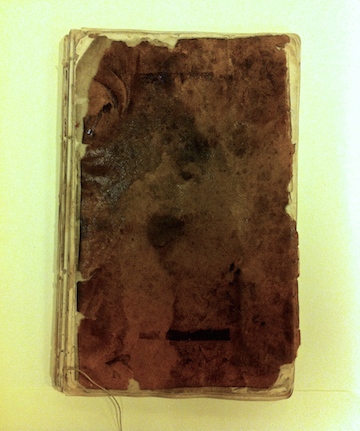

What follows are excerpts from Ickis’ diary (Denver Public Library owns the original as part of its excellent Western History Collection), photographs that correspond with his movements and locations, and some commentary. The roads I drove did not exactly follow the Taos Trail and at one point I lost Ickis’ route entirely. But most of the towns along the way still exist, as do the topographical and hydrological features he mentions—although they bear the marks of more than a century and a half of natural and man-made change.

Ickis and his comrades left Cañon City–where they had drilled during the day and wreaked havoc at night for more than a month–on December 6, 1861. They moved eastward down the Arkansas and then turned southwest along the Huerfano River, where I picked up their trail.

December 11, 1861: “Arrive in camp at the foot of Santa Christe Pass [Sangre de Cristo Pass] at 2 o’clock p.m. It is very cold here keep good fires burning all night.”

December 11 [double dated], 1861: “Commenced climbing the mountains at 6 a.m. the cattle are very footsore and, the ice is very hard on them. have to put ropes [to] the end of the wagon tongue and all hands pull on them to get the wagons over before night. At four PM all over right-side [up] this is the worst pass I’ve seen in these mountains it is high and steep and the snow is deep. Camp for night near an old house which we tear down and use for fuel. Captain found some fault with us for doing so but it was no go down went the house after pulling on ropes all day we were not in a mood for carrying wood ½ mile when there was an old house near by.”

Anyone traveling southward from Denver to New Mexico Territory during this period had to take either the Santa Fe Trail and climb Raton Pass (summit: 7,834 feet above sea level) or the Taos Trail over Sangre de Cristo Pass (now known as La Veta Pass, summit: 9,413 feet). The latter route is forty miles shorter than the former; this–and the fact that the company was ordered to muster into the Union Army at Fort Garland, not Fort Union–may be the reason why the 2nd Colorado took this trail. Due to the weather conditions I was not able to take particularly good photographs of this route, the road up the Pass, or the summit.

December 12, 1861: “Leave camp early and pass Ft Massachusetts [built in 1852 at foot of Blanca Peak, abandoned in 1858] at 9 A.M. arrive at Ft Garland by 11 a.m. F Co 10th reg has not left and we will have to camp for a few days until they leave have a good camp ground”

December 13, 1861: “Visit the Fort today it is a pleasant Fort situated 80 miles from the mts in St. Louis [San Luis] Valley, 20 mls from the Rio Grande it will not quarter more than 3 co. comfortably. the quarters are built of adobes and very good quarters they make warm in winter and cool in Sum[mer].”

Many soldiers and other travelers seeing this region for the first time were fascinated by adobe, a sand-clay-straw-water mixture used as building material for thousands of years. Several of Fort Garland’s original adobe buildings still stand, including these Infantry Barracks. They have been preserved and now house several museum exhibits (many of them recently opened) depicting the Civil War in Colorado, Buffalo Soldiers, and the life and times of Kit Carson (who was in command here in 1866-67).

December 23, 1861: “A co leaves and we move into the quarters they leave Have been mustered into U S service and have received our arms. Spend the day in cleaning rooms and guns. Capt Ford’s Co came in today there are several boys/ in it whom I was acquainted with in the mines the Co is 94 strong. For had a good Co but I do think our Co the best that ever was raised in any country all large men and the most of them damn sharp.”

January 3, 1862, Ft Garland Col Ter: “Recd orders this morning to go to Santa Fe immediately start at 10 a.m. reach [San Luis de] Culebra by 6 P.M. Christ—how sore my feet are I started off with a pair of new shoes on and they have blistered my feet very badly. […] There is snow on the ground and it is rather cool sleeping on the frozen ground with one blanket.”

As you can see from the photographs, the weather on the west side of Sangre de Cristo/La Veta Pass improved considerably during my drive. In January 1862, however, the winter snows kept falling, along with the temperatures.

January 6, 1862: “Leave camp early intending to make Rio Colorado hard traveling the boys who were tight last night feel bad today. I fell upon the ice when crossing a saca [de agua] and hurt my hip did not get into camp until dark.”

Gravity-flow irrigation ditches were and are still common in New Mexico. The communally built and shared acequias move water from creeks or rivers to agricultural fields; the intersection with their water source is known as the saca de agua. The acequia pictured here is in San Luis de Culebra; travelers had to cross over (or through) these waterways as they moved southward on the Taos Trail.

January 9, 1862: “Leave Taos this morning at Sunrise. Pass Santala at 10 a.m. here Sam Pickler gets struck after a Mexican Senorita. Arrive at Ft. Bouquin [Burgwin] by 4 p.m. where we camp this post was vacated last Spring and is now falling down. Are now in the U.S. Mountains the snow is two feet deep and very cold weather.”

Henry Hopkins Sibley was in command at Fort Burgwin when the Civil War broke out; he resigned his commission and abandoned the fort, leaving for the east to join the Confederacy. He would not return to Burgwin again but came close to it when he and his Texans marched through Albuquerque and Santa Fe on their way to Fort Union in March 1862.

January 12, 1862: “Over the Mts all day have to leave one yoke of cattle [at] ‘Flower Chimisal [Chamizal] Valley’ they could not go any farther. Arrive at Lahaza on the Rio Grande. this is the first view I have had of this stream it is very much like Platte river it is muddier, deeper. […] There is a large vineyard here and plenty of the juice.”

Soldiers marching into New Mexico looked forward to seeing the Rio Grande but they were often disappointed when they first spotted this storied waterway north of Albuquerque. I lost Ickis’ route south of Burgwin–it is possible that in 1861-2 the Taos Trail moved around to the east side of Picuris Peak while I took Highway 68 around the west side, and into the Rio Grande Gorge. But Ickis likely saw the Rio Grande near this spot and in any case, to compare the Rio Grande’s northern section to the Platte River in Colorado, as Ickis does, was not a compliment.

January 15, 1862: “Arrive at Santa Fe by 11 am find good quarters. This is Ft Marcy and is commd by [N.B.] ‘Rossell’ Capt of A of the 10th Infty who is a ‘gut’ of the first water Have dress parade every evening and drill twice every day. there is a great deal of formality in Soldiering which I don’t like.”

Fort Marcy–the U.S. government’s first fort in New Mexico Territory–was built in 1847 and almost immediately abandoned. But its location–high up on a hill close to the central plaza of Santa Fe–made it an ideal camp and drilling spot for Union soldiers amassing in the town in 1862.

Although Ickis did not think much of his time camping and drilling among the ruins at Fort Marcy, John Clark, the surveyor general of the New Mexico Territory, had a different reaction. He visited the camp and watched the dress parade on January 17, 1862. “We now have quite a formidable force here,” he wrote in his diary, “three full companies of Mexicans,” “about 100 regulars, [and] a full Company of Colorado Volunteers (a splendid Company under Capt. Dodd).” Ickis and Company B left a week later, marching southward to Fort Craig along the El Camino Real and into battle with Sibley’s Texans at Valverde.

When Alonzo Ickis began his march southward in 1861, the Colorado and New Mexico Territories were characterized by movement; a network of paths, trails, and roads connected towns and pueblos across vast distances. These landscapes of mobility were important sites of economic and cultural interaction for Americans, (New) Mexicans, and Native Americans–and they shaped the events of the war to come.

Kewl! Makes me glad I abandoned a similar project. And you are forgiven for not giving us a call when you crossed the Palmer Divide into the Arkansas River basin (where the Southwest really begins), as we were on the road too, heading for Ouray so G could do the Imogene Pass Run.

So, the 1st CO went down the east side of the Sangres (mustered at Ft Union in Feb/Mar 62, no?, after a forced march?, dang, that book is at work) and the 2nd down the western side. Hmmm, seems that this would be a deliberate attempt not to overwhelm the logistical capacity of the region, which was very, very limited–key difference between West and East during the Civil War. (Didn’t Canby, after the Texans retreated, ask that a number of regiments getting ready to head down the Santa Fe Trail not come, so as not to wipe out his supplies? Again, that stuff is at work.)

Just think of water. As you go down the Taos Trail (dang, been on that road like 100 times), think of the creeks one crosses. Water is the limiting factor in the West, but especially the Southwest.

And, if I remember, there is pretty good evidence that 59-61 was a dry spell, and only broke during the winter of 61-62; think the Rio Grande was in pretty good flood during the spring of 62.

And they did this in Dec/Jan! If I camp that time of year, admittedly to backcountry ski, I would have to have a down-insulated air mattress and a 30 degree bag; they were on the ground with a blanket. Thus the need to go from village to village, I guess, and maybe why they went down the more populated west side.

Again, neat piece of writing, makes me think and realize that sometimes when I’ve seen a piece of land so many times, I sometimes haven’t really been looking at it!

Yes! Logistical capacity may have been the explanation for these divergent routes–or perhaps Garland was more prepared to take in companies at that point (even though the 2nd had to camp out for a couple of days). And yes! Canby was obsessed with maintaining his supply lines–this is the most popular explanation for his reluctance to chase down Sibley and defeat him in a battle. He didn’t want to house and feed all those Texan prisoners.

The 1st headed to Union on that forced march in 1862 because they knew the Texans were already in Albuquerque and Santa Fe–and that Fort Union and the supply line via the Santa Fe Trail and Denver was the Confederate target.

Water–or the lack thereof–is definitely going to be a theme in the book. I just read an account of a Texan riding though the Jornada del Muerto in southern NM who lost 2/3 of the water in his canteen to a leak. By begging and pleading with his comrades he managed to collect another pint, which he had to ration for two days. Unbelievable.

“These landscapes of mobility were important sites of economic and cultural interaction for Americans, New Mexicans, and Native Americans–and they shaped the events of the war to come.”

Just a note, Many “New Mexicans” were still “Old Mexicans.” Many had not become U.S. citizens. Also, in the years after 1848 many Mexicans had migrated into New Mexico without giving up ties to Northern Mexico or citizenship in their “old country.”

Pat, you are so right–I’ve changed the post to reflect this issue of national ties and citizenship in Northern/New Mexico.

Wonderful post, although I admit this made me really homesick!