[Author’s note: an earlier version of this post referred to these objects as “Confederate memorials.” I have changed all references to them here to “White Supremacist memorials” or “memorials to White Supremacy” in order to highlight the origin of their creation, and the belief system underlying arguments for their continued existence in public landscapes].

The debate about what to do with White Supremacist memorials in civic spaces and college campuses was amplified after Dylann Roof murdered nine black parishioners in Emanuel AME Church in Charleston in June 2015. It has been back on the front pages in recent weeks, as New Orleans and other cities across the nation have begun to remove memorials to White Supremacy from their public landscapes.

Civil War historians have been somewhat divided on this issue, as a recent piece in Civil War Times attests. On the one hand, many argue, these memorials are historical texts. We can analyze them in our writing and teaching about the central role of racism in the Confederate war effort, and about the history of white supremacy in America. Some historians – such as Carrie Janney, in her piece for the Washington Post – believe that removing memorials constitutes the erasure of history.

On the other hand, others point out, these memorials honor those who fought for an empire of slavery and currently, they stand in space without analysis, looming over passersby without challenge. As such, they represent the continued oppression of African Americans in political culture, as well as the glorification of white visions of the past, and should be removed from public spaces.

Both sides in this debate stand against a third group, white supremacists who insist that these monuments stand as emblems of “heritage, not hate,” and see their removal as an attack on family history and white identity.

What unites all of the participants in the debate about retaining or removing White Supremacist memorials from civic landscapes, however, is the belief that these are the only two options. We must either keep the monuments where they are (perhaps with a plaque or two to explain their historical context to those who pause to contemplate them), or we must relocate them to storage facilities, cemeteries, or museums.

There are other options, however, that could prompt more community discussions and engagement with America’s racist past and present. I discussed one of these briefly in my Civil War Times piece; here I expand on that idea and propose an additional way not to remove or retain, but to transform memorials to White Supremacy into new representations of American history.

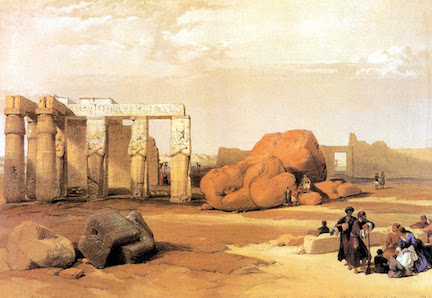

Proposal One: The Ozymandias Project

America does not have many ruins in its public landscapes. Those ruins we do have are preserved in memorial sites devoted to single, spectacular acts of destruction: the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i; the Oklahoma City National Memorial; and the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City. In other places, where campaigns of terror or oppression have been long-lasting, Americans almost always clean up and rebuild, as quickly as possible. This kind of erasure proves (we believe) that we have recovered from the traumas of these moments, and can move on.

One of the realities that the current debate over White Supremacist memorial removal makes clear, however, is that the struggle of African-Americans against the systematic racism of American political and economic culture has not ended. It did not end in 1865. Or 1877. Or 1964-65. Or 2008. Acts of racial violence are one of the tragic constants in American history, and we cannot fully recover or move on from them. We should be reminded of them every day.

The Project: a city government or university administration invites citizens to approach a White Supremacist memorial, take up cudgels, and swing away. The destruction will take however long it takes. It will be a group effort, a way for an entire community – yes, the entire community, ideally – to convert a symbol of racism and white supremacy into a symbol of resistance against oppression. Afterward, the ruins will remain.

Historians could put up a plaque next to the fragments, explaining the memorial’s history, from its dedication day to the moment of its destruction. This signage might be unnecessary, however. Empty pedestals can be quite visually symbolic but ruins are even more so. They tend to convey their messages eloquently in and of themselves, without explanatory text. They represent both the past and the present simultaneously. They prompt those who look at them to think about the differences between then and now, and how they came to be.

Proposal Two: Artistic Upcycling

One of the tactics that white supremacists have used to solidify and communicate their power is controlling the form of and access to public spaces: schools, buses and trains, beaches, university campuses. Taking back White Supremacist memorial spaces is a key part of reckoning with the American past of discrimination; this process also transforms White Supremacist iconography into something productive and meaningful for all Americans.

The Project: Each memorial to White Supremacy is turned over to an African-American artist, who uses the memorial’s materials, exedra, and site however she/he chooses, upcycling it into a new artistic work. This will turn city parks and college campuses into open-air art museums, exhibiting works that engage directly with slavery and white supremacy, and protest against it.

The artists will need funding, of course – the NEH and NEA would be perfect granting institutions for this project, should they survive the Trump administration’s efforts to destroy them. State and city arts councils could also contribute funds to support public art and an ethic of creative reuse, producing the kind of local engagement in dealing with memorials that historians such as Kevin Levin have been arguing for.

Repurposing memorials to White Supremacy through marking has already occurred in several locations, as activists have spray-painted protest messages over chiseled words. Artists have also added works in an attempt to transform memorial spaces. In 2015, for example, the sculptor Pablo Machioli and the activist Owen Silverman Andrews collaborated to place a sculpture of a pregnant black woman at the base of the Lee-Jackson Memorial in Baltimore. This sculpture was quickly removed, however.

Like the Ozymandias Project, permanent artistic upcycling would invite visitors to consider the cultural values that brought the White Supremacist memorial into being, and the process through which it can been transformed into a new American political aesthetic.

***

Both of these proposals are, admittedly, politically impractical. They would likely provoke violent responses from white supremacists and endanger the lives of participants.

It may do us good, though, to imagine a society in which proposals like these would be put into action locally, and would be publicly funded; to create for ourselves a society that urges Americans to reckon with the ugly, violent, repressive structures and events that undergird our history; and to work toward a culture that makes new spaces for creative engagement with that past, providing opportunities to change our future.

Featured image: White Supremacist memorial on North Kings Drive in Charlotte, which has since been covered to prevent marking.

History is written by the victors, it is said. Since Love will ultimately win, let us repurpose any visible monuments to the horrid and selfish side of US history to acknowledge and deeply regret the wrongs that were done in the name of ‘white supremacy’. Community expressions about this history might be invited, along with the art, sharing and outreach proposals that have already been made and evidence of the community’s determination to move forward into peace, standing on the side of love.

I love the up cycling idea. Then the dialogue itself becomes the history. Thanks for showing us how to think about this in new ways.

I love the first idea but, as you say, that is not going to happen as it is more provocative than just removing them.

Sadly, it will not.

I love it. Thanks for a provocative post! Here’s another wacky idea actually implemented in Budapest. Take some of the old statues/memorials (communist ones in their case) and place them in a park of their own (outside town), along with a museum on slavery/the Civil War/Reconstruction/Jim Crow/Lost Cause fetishism, the society that created these monuments, reasons for taking them down, etc. Here’s a link to pictures and a bit about the park in Budapest, called Memento (or Statue) Park: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/picturegalleries/6407349/Budapests-Memento-Park-in-pictures.html?image=13#PhotoSwipe1501530422098. (Of course, I realize the Confederacy is a much more fraught topic in the U.S. than the communist era is in Hungary. But still, an interesting way to deal with old irrelevant monuments!) The only communist era statue they left in Budapest is memorializing the Red Army’s ‘liberation’ of Hungary, which is in the square in front of the U.S. Embassy (purposely, I’m sure), which the Hungarians agreed to keep in exchange for the Russians tending to the graves of the Hungarians who died fighting in the USSR in WWII. This statue is now joined by one of Ronald Reagan, lending a rather surreal element to the square (which is called Liberty Square). And then there is the highly controversial recent WWII memorial (and counter-memorial) at the other end of the square. (If you are interested in more on that, see my blog post on “Public Memory and Public Squares” (http://emlitwicki.org/my-hungarian-adventure/public-memory-public-squares-in-budapest/).

Thanks for these great links, Ellen! I like especially the Szabadság Szobor, which you describe in your post – this seems like the kind of productive transformation that I’m arguing for here. Other folks – public historians in particular – have argued for creating a sculpture park/museum, but I am not in favor of this, as it is basically just another form of removal. With monuments like these, I think it’s important that they be visible – but reshaped – in public places, accessible to all.

I like this way of thinking although I struggle a bit, falling as I do between the first two groups of responders (don’t want erasure but neither do I want things left alone). The Ozymandius approach feels deeply cathartic but extreme and I fear that piles of rubble, left alone, would become sites of veneration for precisely the groups that venerated the monuments in the first place. I would push the second approach towards repurposing the land and site, perhaps with art, but also with purpose – crowd out the monument with objects or spaces that promote inclusive activity (I don’t know, performance spaces? Open-air kitchens?) in order to diminish the visual power of the monument itself.

Yes, the ruination approach is definitely extreme – and it could have the unintended effect that you suggest. I would love to see what artists and landscape architects could do with this spaces, in a repurposing project like the ones we are thinking of …

Sarcasm?

Do you mean, is this post sarcastic? No. Deliberately provocative? Yes.