As Dan and I entered the stark white exhibit space at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston this past weekend, we heard the sounds of spring. We ambled further into the exhibit and the birds chirped more loudly, the insects buzzed more insistently. It felt less like a hallucination then, and more like walking right into the warm, humid South.

What we were hearing was Kevin Beasley’s sound installation, As I rest under many skies, I hear my body escape me (2014), one of the most compelling works in the ICA’s new exhibit “When the Stars Begin to Fall.” This show, a contemporary art exhibit that “gathers thirty-five African-American artists of different generations who share an interest in the American South as both a real and fabled place,” opened in early February and runs through May 10.

Beasley’s As I rest joins mixed media paintings, photographs, and sculptures made of found materials. Many of the artworks depict southern places or evoke specific moments in the South’s past; the most moving and effective of these are several video installations, which convey the peculiar horrors of the antebellum plantation landscape.

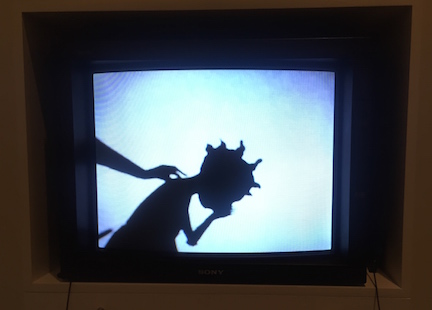

Kara Walker’s 8 Possible Beginnings, or the Creation of African-America; a Moving Picture (2005), puts the artist’s famous silhouettes in motion, acting out 8 scenes in which slaves are thrown overboard from a trading vessel; swallowed by “The Motherland”; pursued and raped by a slave owner; tended to by midwives as they give birth to what looked to be a hybrid of a human and a cotton boll; and lynched by Br’er Rabbit and Br’er Fox. Walker’s puppeteering is deliberately amateurish and awkward (her hands are often appear on-screen) and she uses the silent film style, with grainy and telescoped filters and dramatic musical accompaniment. The result is a stark and unblinking depiction of the violence of slavery and the dangers of mythologizing the South in popular culture. The film, like most of Walker’s work, is both shocking and beautiful; you cannot look away.

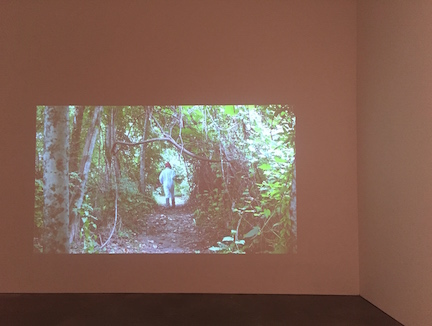

Even more unsettling, though, is Rodney McMillian’s A Song for Nat (2012), a six-minute film that follows a man dressed in a white jumpsuit as he stalks through a forest. He wears an Iron Man mask and carries an axe – he is a modern Nat Turner. He comes upon a “Big House” and walks around it, trying various doors and windows. In the end, he walks off, continuing his search. The visual incongruities of this man, his anonymity, the lush forest (the sounds of Beasley’s installation acting as an accompaniment), the house, and bright sunny day creates a feeling of dread. It reminded me of certain horrific scenes in “True Detective,” one of the more evocative and immersive television series to depict the South and its violent histories in recent years.

These artworks were probably the most compelling to me because I am most interested in the place of the past in Southern culture, and in the history of slavery and resistance to it. They also use the sounds and the fecundity of the southern landscape to connect the viewer to the material realities of the South, in unexpected ways.

But there are works in the exhibition that seem only tangentially related to the larger theme of regional distinctiveness.

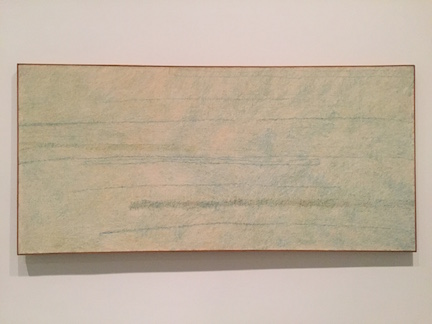

One example is McArthur Binion’s beautiful abstract painting Circuit Landscape No. II (1973). The caption argues that the horizontal lines of the painting “recall the landscape and light of the artist’s native Mississippi” and the “near-ritualistic manner of applying pigment mimics the repetitive motions in certain types of manual labor.” Now, I’m not one to decry creative close readings but without the caption, Circuit Landscape No. 11’s southernness is not particularly evident.

This brings up an important question about the exhibit, and its assumptions: what is it, exactly, that makes art – and an artist – “Southern”?

African-American culture and history are dominant themes of the exhibit – and it is refreshing to see so many African-American artists gathered in one place. There are many works that evoke religious belief and expression (several of the artists began to create works after a religious revelation of some kind). References to other forms of southern artistic expression – minstrel shows, the gothic narrative, vernacular architecture and textile production – abound. In addition, many of these artists were born in the South (although most of them have spent the rest of their lives elsewhere).

Must the artist live in this region and experience its deep histories to be considered “southern”? Must the work depict the South as a unique place? Or must it engage with other forms of southern culture? Must it be devoted to examining the nature of Southernness itself?

Perhaps the very fact that “When Stars Begin to Fall” has prompted me to ask such questions is evidence of its success — in complicating categories of and definitions of art, African-American culture, and southern history.

Featured image: Rudy Shepherd, The Superdome (2011)

This makes me want to blog about the exhibit in which the images in my book, Dreaming of Dixie, were “reimagined” by modern artists. I’ve got the exhibit catalog. I never thought about this until now. Great post!

Karen, that is amazing that modern artists recreated the images in your book — and that there was an exhibit! Please do blog about it, and post some photos!