Figuring out the best structure for your project is a vital part of the writing process.

For most academic historians, the basic structures for journal articles, masters’ theses/Ph.D. dissertations, and books are pre-determined: an introduction with a descriptive opening, a historiographical turn, and then argument-driven sections, followed by a conclusion.

For historians who would like to or need to stick to these traditional structures, how do you organize the sections?

And for historians who want to break from this traditional structure, how might you go about it?

For a while now, I’ve been recommending to my structure-stymied friends and colleagues an exercise called the Five x Five.

A colleague of mine in the History and Literature program at Harvard first introduced me to this exercise; she used it with her seniors writing undergraduate theses.

It works like this.

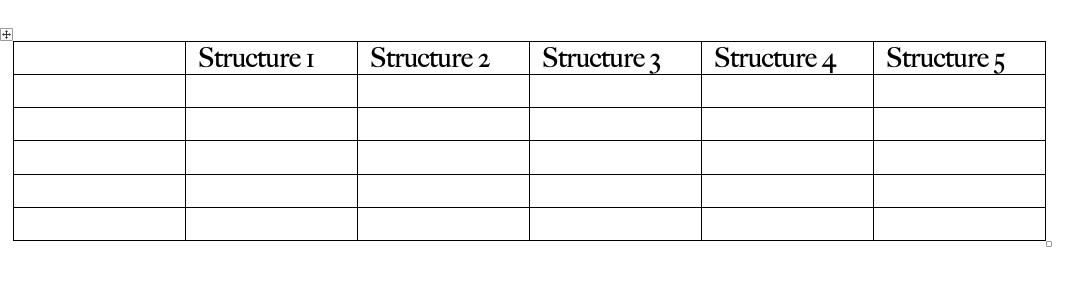

Take a sheet of paper and create a grid of five squares across, and five squares down.

Label every square across “Structure 1”, “Structure 2” etc.

Label every square down “Section 1,” “Section 2,” etc.

Start filling in the grid with five possible structures for your project, each with five sections. You may have more than five sections for any given structure. That’s fine. And you may think of more than five structures. That’s great.

If you are an academically trained historian, the first two structures will almost always be “Thematic” and “Chronological.” But there’s a lot of room to play around with the sections for these structures.

And don’t stop at just those two.

The point here is to push yourself to think of all five and actually lay them out. They can and will likely get a little zany. And you are not required to commit to any of them.

What the Five x Five exercise does is help push you past the expected, and open up new ways of thinking about structure and argument. It forces you to get creative.

Hopefully, this exercise will help everyone with a writing project find the right structure for them.

How will you know? I know this sounds lame, but you’ll know it when you see it. It’s like when Watson and Crick were messing around with the structure for DNA. When they finally hit upon the double helix, they said they just knew it was right—because it was beautiful.

Go find that beauty, writers. And let me know how it goes!

Could you please include an example? Thanks.