You probably think that I’ve got some sort of obsession with vampire TV shows and movies. But have you considered that perhaps this is because recent vampire TV shows and movies have an obsession with history?

Most historians have not paid much attention to vampires; literary critics, on the other hand, have lavished attention on them. In 1990 Stephen Arata urged his colleagues to move beyond psychoanalytic analyses and to consider the historical contexts in which vampire literature was written and read. Since then, scholars have examined the historically contingent constructions of empire, race, gender, sexuality, class, and region in vampire literature and media. These readings of vampires are compelling; but they often ignore the ways that recent vampire shows (and others with supernatural characters) actually use history–as plot and narrative, illuminating but also erasing many cultural tensions and conflicts.

Backstories

The Vampire Diaries (CW, 2009) is a show that uses a host of familiar plot devices: an orphaned protagonist, a mysterious stranger, a love triangle involving “good” and “bad” siblings. Set in Mystic Falls, Virginia (and filmed in Georgia) the show establishes its Civil War backstory almost immediately. Two of the protagonists, Stefan Salvatore and Elena Gilbert, have a U.S. history class together and Stefan demonstrates both his historical knowledge and his rebellious attitude by correcting the teacher’s depiction of the Battle of Willow Creek, which took the lives of more than 300 soldiers and civilians in the town in 1864. Elena is intrigued; Stefan seems way too good-looking to be a history geek.

She grows even more suspicious when she sees the original guest registry of the first Founders’ Ball that includes Stefan’s and his brother Damon’s names, and a tintype of a woman who looks exactly like her, dated “1864.” In episode 6 (entitled “Lost Girls”—an homage to the 1987 vampire movie classic “The Lost Boys”), Stefan explains his history to Elena, as they wander the ruins of his family’s plantation house (ruins!).

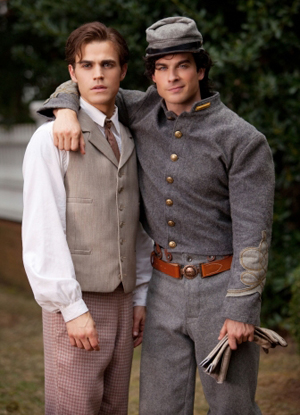

The show flashes back to wartime: Damon is wearing a Confederate uniform; Stefan is not, for reasons he does not explain. They are both flirting with Katherine, Elena’s doppelgänger, who is the archetypal Southern belle: she’s beautiful, feisty, and wearing a corset and a hoop skirt. She’s a 500-year-old vampire, but she represents herself as a “poor orphan girl from Atlanta. I lost my family in the fires” (it’s worth noting that the show also has an obsession with Gone with the Wind, reenacting many scenes from that film with both vampire and human characters). Katherine turns both brothers and then lets them think that she has been burned in the church with the rest of the “civilians” (actually, also vampires) during the Battle of Willow Creek.

The Vampire Diaries is not the only recent show to root protagonists’ backstories in the American Civil War. In the fifth episode of the first season of True Blood (HBO, 2008), after vampires have “come out of the coffin” and made themselves known to humans, the vampire Bill Compton agrees to speak at the monthly meeting of Bon Temps, Louisiana’s Descendants of the Glorious Dead.

He tells stories about life in Confederate camps and in battles, and articulates a Lost Cause narrative of the war: “It was there that we learned the value of human life, and the ease with which it can be extinguished. … Uneducated as we were, we knew little of the political or ideological conflicts that led to this point. … But going to war was not a choice for us. We believed, to a man, that we had a calling to fulfill, a destiny handed down to us from above.” He is flanked by a U.S. flag, a cross, and several photographs of Confederates, including Private Edwin Francis Jemison (Co. C, 2nd Louisiana) and Robert E. Lee.

Interestingly, in the current (and final) season of True Blood, the show is regularly integrating flashbacks to Civil War Louisiana. In these more recent episodes Bill is portrayed as a member of the planter elite (a commissioned officer, not an uneducated volunteer), a soothsayer (“This is a lost cause! The Yankees have better artillery, more sophisticated weaponry than we do. What they will destroy is our town, scorch our land, our livelihoods”), and a friend to Bon Temps’ slaves (he is caught trying to lead a group of fugitives out of town and to a safe house). The show, then, revises Bill’s own history, giving him much more complicated motives for his wartime service. It also erases Bill’s history of slaveholding, and any suggestion that he might have gone to war to defend the “divine destiny” of the white antebellum South.

Bill’s vampire backstory also tracks with the Salvatores’ in The Vampire Diaries. At the end of the war Bill tries to take a short-cut home, loses his way, and ends up at the cabin of a woman who tells him she is a Confederate widow; she has not heard from her husband in seven months and assumes he died fighting with the 13th Louisiana. Her name is Lorena—an inside joke for Civil War historians and enthusiasts. When Bill refuses to take advantage of her, Lorena is so impressed with his nobility that she reveals herself as a vampire and turns him so they can live together forever.

What to make of these shared narratives, of white “Southern” women manipulating white Southern men and then turning them into vampires? This could reflect the twenty-first century context in which these shows are produced; power is most often determined by age rather than gender or race or sexual orientation. These shows also suggest that there is power to be found in certain historical moments. The Civil War, as a time of tremendous mobility and chaos, created opportunities for those who might have otherwise been vulnerable: single women, supernaturals. Wartime exigencies also allow these characters to explain their circumstances—sudden and inexplicable deaths, people gone missing—through narratives that are intelligible to both other characters in the show and to viewers at home.

Living (well, actually, Undead) Histories

As immortal vampires, Stefan and Damon Salvatore and Bill Compton are also living histories (as much as the undead can be) in the present day. When Stefan corrects the history teacher about casualties at the Battle of Willow Creek, he speaks with knowledge gained not from books but from actual experience; he was there. And when the high school students put on dances with historical themes (the 1920s, the 1950s), the Salvatores need only root around in their own closets for appropriate outfits. These situations are often played for laughs and there are no historical arguments or analyses here; flashbacks in The Vampire Diaries usually work only to explain relationships or to allow the actors to appear in radically different hairstyles and costumes. History is not exactly history in this show; it is memoir.

True Blood engages a bit more with the appeal of the past in the American South. The church is packed for Bill’s DGD talk; many people are there because they are curious about vampires, but there are a good number who attend because they seek direct contact with history—which only an immortal vampire can provide. One audience member asks about Tolliver Humphreys, his great-great grandfather who, like Bill, fought as part of the 28th Louisiana.

Bill proceeds to tell the story of Humphreys’ death; a Union sharpshooter killed him as he attempted to rescue a fellow soldier, a boy about twelve years old who was lying wounded on the battlefield. At this news, Humphreys’ descendant’s eyes fill with tears and the audience utters a collective sigh.

Vampires also serve as historical texts themselves, revealing the “truths” of events, which have often been masked by local officials and academics (a large number of human villains in The Vampire Diaries are college professors). Additionally, historical texts confirm their existence. In The Vampire Diaries, after Elena first sees Stefan’s and Damon’s names on that 1864 Founders’ Ball list, she confirms her suspicions by watching a 1950s news report in which Stefan appears, ghostlike, in the background.

And in True Blood, at the end of Bill’s talk, the Mayor—who has “been digging in the archives this week”—hands him a tintype labeled “W.T. Compton and Family.” “Can you tell us if this is a picture of you?” he asks. Of course it is. And in the third episode of this final season, Bill remembers the day he and his family posed for that photograph. For viewers who have watched the show from the beginning, this image sparks another kind of flashback, helping to build the show’s own internal history.

The Supernatural Archive

Photographs and other texts appear with surprising regularity on these shows, and in others that depict supernatural beings and story lines. In The Vampire Diaries, the characters often use manuscripts—diaries and grimoires (magic books)—in addition to objects in order to understand the past, and to fight evil.

This use of texts reminded me of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB, 1997) and the significant role the high school library and later, Giles’ apartment and the magic shop play as sites of knowledge acquisition. As literary scholar and blogger Mark McCutcheon has written about reading and research in Buffy, “it’s rare that the research doesn’t pay off, in one way or another [in the show]; most often, it pays off in critical discoveries and insights, knowledge of the situations, events, and adversaries they face, of the histories that have produced them, and sometimes even of vital knowledge of self.”

The recent hit show Sleepy Hollow (Fox, 2013), which also blends historical and supernatural narratives, continues this trend. In it the protagonists (Ichabod Crane, who died in 1781 but has been brought back to life through magic, and Abbie Mills, a police lieutenant) investigate baffling mysteries—all of them a result of dark forces gathering in Sleepy Hollow. Abbie has visions and Ichabod has Revolutionary-era memories but in order to solve these cases, they they sit down together and do some good old-fashioned manuscript research. They visit historical societies in search of information and in the police archives at an abandoned armory they create their own library of historical texts. The plat maps, letters, objects, video and audio files, and other archival documents that they collect lead, as in Buffy, to critical discoveries that allow them to defeat supernatural beings and forestall the apocalypse. There is value in historical texts in these shows, and in the ability to locate and analyze them.

Supernatural characters are increasingly popular on television and in film but not all of these media narratives engage overtly with history. However, the overlapping Civil War contexts and the turn to archival research in shows like The Vampire Diaries, True Blood, and Sleepy Hollow suggests that the conflicts, fears, and desires—both personal and political—that these shows dramatize are rooted in the historical imagination.

Vampires = rad. History = rad. That these two would eventually meet seems quite natural.

I think you could do an entirely separate post on the Supernatural Archive (or multiple posts, even). Several novels that immediately come to mind are The Historian, The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, and A Discovery of Witches.

Yes! Or perhaps *you* could write Historista’s first guest post! ; )