Just getting to the 9/11 Museum is quite a production. Most of the surrounding area is still a construction site, and so after you leave the subway station you walk all the way around it, hemmed in by tall chain-link fences, before you come upon the 9/11 Memorial: the two gigantic waterfalls in the footprints of the Twin Towers, marked off by dark panels bearing the names of the dead.

I did not have the negative response to them that Adam Gopnik did; to me, they effectively evoke several traditions of national feeling and memory at once: the sublimity of waterfalls, the monumentality of civic fountains, and the minimalism of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Gopnik is right, however, that it is almost impossible to feel contemplative here; the crowds are immense, and the angle of the panels invites both adults and children to lean forward onto them in a casual way that seems disrespectful.

You turn from the Memorial and make your way through the rope line outside of the Museum, moving slowly through a security checkpoint (yes, you have to take off your belt if you are wearing one) before walking into the 9/11 Museum’s Entrance Hall. Here, everything is bright. The walls are painted white and the roof soars up into a jagged point, the light pouring through large glass panels. But as you move downstairs to the Concourse Lobby, you descend into darkness.

9/11—as a horrifying moment of incredible violence in American history—poses challenges for those who seek to memorialize it. It diverges from memorial traditions established in the wake of the Revolutionary and Civil Wars because the usual tropes that emphasize glory, honor, and sacrifice do not apply in the same ways. Instead, its meanings are unstable and extremely complex. In this particular case, there is also the issue of timing. 9/11 is an event so recent and vivid in most adults’ memories that the objective distance that memorialization requires seems impossible. And as David Kieran has pointed out in his excellent new book Forever Vietnam: How a Divisive War Changed American Public Memory, Americans are always “revising and redeploying memorial practices” to answer questions that often have nothing to do with the event being commemorated.

The 9/11 Museum’s solution to these challenges is to create two narratives: one that emphasizes the destruction of people and of architecture (the “victims”) and one that tracks the experiences of witnesses (the “survivors”). These narratives are not explicitly presented in textual materials, but they become obvious as you move through the different sections of the museum.

From the Concourse Lobby you continue to descend, walking down a ramp in the near dark, encountering a series of introductory exhibits: a “soundscape” of voices (people remembering where they were at that moment, on that day) and a series of projected images of people staring up at the sky in horror, their hands covering their mouths; a battered “Heritage Trails New York” sign that survived the collapse; two gigantic illuminated photographs, juxtaposed: one of lower Manhattan at night (with Towers intact) and one depicting the burning Towers moments after the planes hit; the signs of The Missing projected onto pillars and a large blank wall.

The ramp is eerie. If you stand still in one place, you can watch people just drifting down, down, down, all walking in the same direction, pausing only briefly before moving on. It is an experience reminiscent of watching the masses of people streaming away from the Towers in the afternoon and evening of 9/11, walking home in a daze, covered in ash.

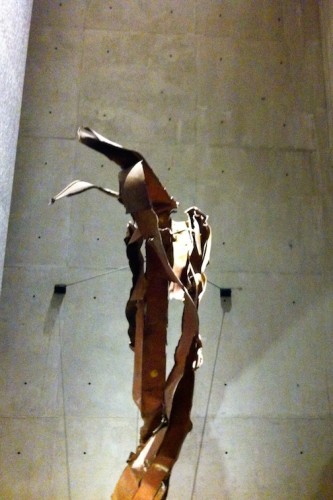

There are viewsheds every now and again: at one point you can pause on a cantilevered platform to look out over Memorial Hall, a cavernous space whose centerpieces are the slurry wall and “The Last Column”—a 36-foot tall fragment of steel that supported the inner core of the South Tower. It survived the collapse and became a memorial in and of itself.

At another point, you can take in a massive cement wall that contains a work entitled “Trying to Remember the Color of the Sky on That September Morning,” hundreds of small, square sheets of blue and purple paper that surround a quote from Virgil: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” It is not until you peer at the plaque on the far end of the wall that you realize that behind it lie the remains of people who died on the planes and in the Towers.

You also realize that when you walk down the ramp from the brightness into the dark, you are moving into Ground Zero. The museum’s central exhibit halls are entirely underground, occupying several stories that used to be parking garages under the World Trade Center, and marking the Towers’ absence with the remnants of box columns anchored into bedrock.

In addition to these “excavation” sites, the main floor contains a variety of spaces: an education center; an “In Memoriam” room displaying a photograph of each person who died (they are arranged in alphabetical order and are all the same size); a gallery showing a variety of photographic and multi-media installations; and a Tribute Walk that presents a selection of works produced in memoriam: quilts, a large ceramic urn, a mural painted by fourth-grade students from Charleston, South Carolina.

Through the Tribute Walk and the objects it displays, memorialization itself becomes a part of the story of 9/11, a central component of the “survivors” narrative that links it to the “victims” narrative. This practice—the production and donation of objects later integrated into memorial sites—is central to historical commemoration in the post-Vietnam world. As Kristin Hass explains in Carried to the Wall, visitors began to leave objects at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial after it was dedicated in 1982; Dave Kieran argues that visitors now expect this kind of interaction at memorial sites.

The temporary Flight 93 Memorial in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, for example, was created almost entirely of such objects, a form of spontaneous commemoration that also appeared in Copley Plaza after the Boston Marathon bombing. The permanent Flight 93 Memorial, Kieran notes, integrates spaces for leaving items of remembrance, fostering a connection between visitors and the victims of the plane crash, through material objects.

The 9/11 Museum does not offer such opportunities but it does encourage visitors to become part of the memorialization process. You can record your memories of 9/11 or write messages on tablet screens that are then projected below the slurry wall, a continuously produced and ephemeral graffiti of remembrance.

There are many other objects on display whose purpose is to represent these kinds of commemorative and preservationist tendencies among witnesses and survivors.

Most of them are twisted shards of steel.

You encounter the first in the Entrance Hall: two towering tridents, columns that once supported the exterior of the North Tower. These are meant to represent endurance and survival, testimonies to both architectural engineering and to human attempts to save the fragments of the past. The label for the Tridents reads, “Anticipating the likelihood of a memorial and museum about the September 11 attacks, staff and consultants working for the owners of the World Trade Center, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, painted SAVE on these trident during the post-9/11 cleanup, designating them for preservation.”

Other objects, like a fragment of a column from the South Tower bent back over itself, are meant to indicate the extreme violence of the explosions and collapse, the intensity of the heat and the pressure that destroyed these massive buildings. This is emphasized as well by the inclusion of a huge chunk of “composite” in the main exhibition space: the compressed remains of four stories of one of the Towers, compacted into a wedge of striated material four feet high and weighing between 12 and 15 tons.

Then there is the Last Column, towering like a lone chimney in the middle of Memorial Hall, spray-painted with FDNY engine and NYPD station numbers, plastered with photographs of the fallen and other memento mori. A nearby display case reveals that most of these images and objects on the Last Column are replicas; the originals were removed for preservation. The Column is therefore a folly ruin, exemplifying both destruction and construction at once and exemplifying a long-standing trend in commemorations of the nation’s dark histories.

In the midst of all of these shards (which together create a sculptural garden of destruction) there is a central exhibition space, which displays thousands of objects meant to illuminate the events of 9/11 and their context. It is contained entirely in the footprint of the North Tower and you access it through a single set of revolving doors.

When I was there—a Saturday afternoon in the summer—the exhibition was packed with so many people that I could barely move. The passageways are narrow and they wind around large display cases of objects. If one person stops to read a tiny label (and they are tiny—and shiny, which makes them extremely difficult to read at any distance or angle), the entire crowd comes to a halt. The galleries resemble a maze, with tiny side-rooms with more focused content (one, hauntingly, displaying only photographs of people jumping from the Towers, projected in a continuous loop). The combination of the dim lighting, crowds, and hundreds of objects jammed into display cases is claustrophobic, and makes you want to flee.

Perhaps this is the point. Perhaps the museum designers wanted to create a “mood” in this exhibition, to push visitors to experience the chaos and the disorientation of being in the Towers on that day. If so, they have succeeded to some extent. But one can never really feel the terror or the desperation of the people trapped in the Towers or on those planes; and to suggest that one could is ridiculous. In addition, the layout and approach in the exhibition prevents you from really absorbing the nature of these objects and their meaning, and their intimate stories of love and loss.

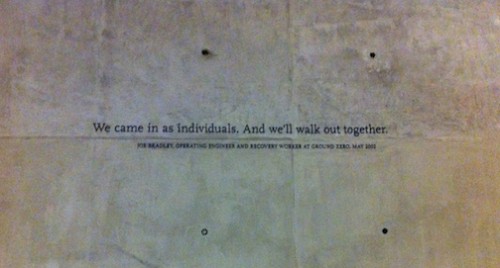

When you finally break free from these exhibit rooms and walk toward the Museum exit, you pass by a photograph of the Last Column being transported up a ramp, the last object to leave Ground Zero after the cleanup. Text on the wall reads, “We came in as individuals. And we’ll walk out together.” “Amazing Grace” plays as you ascend an escalator, clearly meant to replicate that ramp (which was originally made out of compressed debris). You can’t help but roll your eyes; it’s just all too much. And this is not how we should feel in such a place.

The only time I was moved to tears was outside the In Memoriam room, listening to people read the names of their family members and friends who died, and how they knew them. “My uncle, …” “My friend and colleague …” “My dad …”

These voices—sad and proud and lonely—managed to convey what the vast halls and thousands of objects in the museum could not: the intimate knowledge of lives lived and lost, warm and personal and suggestive of all kinds of things left unsaid.

Great review, Megan. Beautifully written, thoughtful, powerful. Thanks, I will be sharing with my graduate students.

Thanks, Judy!

Hello. Thanks for the thoughtful review of the 9/11 memorial and museum. It is especially timely given I visited it as well a week ago today. I found it a moving experience, although the museum is consciously influencing visitors toward an emotional response. As I indicated in my own review, I’ll be curious how the museum and memorial age, especially as the visitors increasingly are people who do not have personal memories of 9/11. I found my own visit very much influenced by the fact I lived through 9/11 and the sounds and sights of the museum evoked by personal memories of that day. I am very curious how the museum and memorial are and will be experienced by persons without those personal memories. Indeed, it will be interesting to see how future events will shape how people perceive 9/11. If in the future there are events as bad or worse than 9/11 will the museum and memorial lose their significance? Even now as time goes on, the event does not seem as wrenching and outrageous a decade later than it did in the weeks and months that followed the 9/11 attacks. Will people in the future even care about 9/11? Should they? We shall see.

Don, what a coincidence that we both visited the museum last week, and that we both begin our posts in the same way (and with almost identical photographs)! It is indeed fascinating for those of us who think a lot about historical memory production to encounter this site memorializing an event that took place in our own time. I’m not sure about what future visitors will think. Do the massive casualties of the World Wars minimize the impact of Civil War memorials?

Hi Megan. Quite a coincidence, indeed. An excellent question about Civil War memorials and the mass casualties of the World Wars. No doubt the World Wars had an impact on Civil War memory and memorialization. It seems to me that time and the horror of the World Wars would have softened for succeeding generations the impact that Civil War memorials would have had for the Civil War generation. (I know I find such memorials often quaint and romantic–I doubt the Civil War generation saw them that way.) I am not sure how time will impact the 9/11 museum and memorial. No doubt time will soften their impact as well, but it will depend on the whatever relevant events occur down the line. But it will be interesting to see how people see the 9/11 memorial and museum, 25, 50, and 100 years down the line, assuming they are even there.