A few weeks ago, I went with Kevin and Michaela Levin to see Suzan-Lori Parks’ new play, Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2, & 3) at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The play is part of a longer cycle (there will ultimately be nine parts) but this segment focuses on the American Civil War; it is at the A.R.T. through March 1 and if you are in the Boston area, I recommend you see it.

Part 1 takes place in the slave quarter on a plantation in West Texas. Parks lived in Odessa for a time as a child but in this first production of Father Comes Home, at least, the location of the plantation does not seem to matter to the play’s themes. Most of the action in this first segment focuses on a major decision that the protagonist, a slave named Hero, must make: will he accompany Boss Master to the war, or won’t he?

SPOILER ALERT. Part 2 takes place in a forest in the trans-Mississippi theater, where Hero, Boss Master (now The Colonel) and a Union prisoner named Captain Smith negotiate the terms of their power over one another.

Part 3 takes us back to the plantation, as several slaves (and some fugitive slaves who are pausing in flight) await Hero’s arrival home. SPOILER ALERT (though perhaps obvious from the title). He does indeed arrive home but the war has changed him in important ways, and he is now alienated from the slave community of which he was a part.

The play is part of the A.R.T.’s commemoration of the Civil War sesquicentennial through its National Civil War Project, which supports collaborations between multiple theaters and has funded several performances and research roundtables that focus on the war and wartime culture.

Like many of Parks’ plays, Father Comes Home is epic yet deeply personal, and dense with dialogue. It is, quite deliberately, a mash-up of the historical and the modern, both in language and in action. And through it, Parks plays with common perceptions of American slavery and the connections between warfare and emancipation.

Not Your Civil War

Many of Parks’ works engage with questions of racial inequality and African-American life; this is her second play (that I know of – there may be more) with connections to the American Civil War: her Pulitzer Prize-winning Topdog/Underdog (2002) depicts the conflicts between two African-American brothers named Lincoln and Booth; “Link” is an Abraham Lincoln impersonator; he works at an arcade, sitting in a theater while paying customers assassinate him, over and over and over again.

So clearly, Parks is interested in this historical moment, and its significance in African-American history. Make no mistake – neither Topdog/Underdog nor Father Comes Home is a “historical” play, and anyone looking for references to specific battles or discussions of wartime policy in Father Comes Home will be disappointed.

The actor who plays Boss Master in the A.R.T. production told us during the talk back after the show that while they were in rehearsal, he began to tell Parks about the research he had done on the war and the battle of Shiloh (which is referenced in the play), and she interrupted him, saying “No, no, no. That’s your Civil War. Not this Civil War.”

This is a fascinating assertion, and it suggests that in Parks’ view, “the Civil War” had a different meaning and chronology for southern slaves than for southern and northern whites. Most historians of the conflict would agree with this assertion, I think.

This comment also reflects Parks’ interest in the classical roots of theater. The characters’ names (Hero, Penny, Homer) and the presence of a kind of Greek chorus in Part 3 suggest that for Parks, the Civil War is literary in nature: the characters in Father Comes Home do not exist to illuminate Civil War history; instead, a war exists, internal to the play, which creates a series of crises that offer opportunities for transformations – within the hearts and minds of individuals, and within the slave quarter.

Making Choices

The play is also a bildungsroman (a voyage of discovery) and so at several points in the play the characters, almost all of whom are slaves, make decisions that determine their own fates. As noted above, Part 1 is devoted to discussing, predicting, and responding to Hero’s decision to go to war. Both Kevin and I were skeptical that Boss Master would actually give Hero a choice in the matter; but again, this is not a historical play in the usual sense.

Instead, the war serves as a fork in the road for Hero and for the slave community. Although Boss Master has promised him freedom before and he has done terrible things to his fellow slaves to try to secure it, Hero chooses to believe in Boss Master’s promise in 1861: if Hero comes along, Boss Master will emancipate him when the war is over. In the end, Hero chooses Boss Master – and his own freedom – at the expense of his relationship with his “almost wife” Penny, and his friends in the quarter. In this first part and in Part 3, the play reminded me of the film 12 Years a Slave, which exposed the ways that power dynamics within slavery could bring slaves together but also distance them from one another.

While Hero is gone pursuing his own freedom, the slaves of the quarter make their own choices. We discover in Part 3 that most of them have taken advantage of Boss Master’s absence and wartime chaos, and have fled. Only Penny and Homer have stayed. Penny is waiting for Hero and Homer is waiting for Penny; they have found solace in one another’s arms. They have also sheltered a group of runaways (the aforementioned Chorus) who are passing through the plantation on their North (it is unclear if this “North” is Colorado or New Mexico or Indian Territory but again – it’s not a historical play in the usual sense).

These are choices that involve great personal risk in this mid-war period. Lincoln has issued the Emancipation Proclamation but the slaves here have not yet heard about it; at the end of the Part 3, after his friends desert him, Hero takes a crumpled sheet of paper out of his pocket. He had meant to read Lincoln’s Proclamation to them, to show them that the war had given them “a chance at getting something,” just like it did for him. But they have taken their freedom for themselves before he can.

Wearing Uniforms

Promotional photographs for Father Comes Home show Hero in a Confederate uniform and both Kevin and I were a little nervous about how the play was going to portray southern slaves working for Confederate officers and the Confederate army. It was a relief when, in Part 2, it became obvious that Hero is working as the Boss Master/the Colonel’s valet, and not taking up arms for the Confederacy.

But as the play continues it also becomes clear that uniforms – both Union and Confederate – play a significant role in Father Comes Home. In Part 2, the Union prisoner is wearing an officer’s coat, which leads the Colonel to believe that he is a valuable commodity to trade. That Captain Smith’s coat is much too big for him is a detail that escapes the Colonel’s notice – but not Hero’s. Smith’s uniform therefore signals a rank that is in fact not his own, conveying the ease with which one could manipulate and undermine the perceptions of others during wartime.

Civil War uniforms in Father Comes Home also expose the superficiality of martial manhood. In Part 2, the Colonel wears an elaborate, decorative Confederate uniform – and a giant white feather that he lovingly keeps in a fancy box – with pompous pride. As he struts around the stage, the audience laughs, and mocks him. And when Hero first puts on the coat in the slave quarter in Part 1 – saying, “I look all right!” – and begins to march with exaggerated swagger, he also undermines the martial manhood such a uniform promises.

Slavery and Freedom

Part 2 of Father Comes Home contains several direct and unblinking exchanges about master-slave relationships. The Colonel discovers that his Union prisoner is an officer in the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. He then boasts that his ownership of slaves brings him closer to them than this northerner’s command of black soldiers ever could. As evidence of this, he states that Hero “came with me without a second thought.” This statement is belied by the entirety of Part 1 of the play, of course. The Colonel obviously knows nothing about Hero as a man and cannot see him as anything other than his slave.

Then Colonel asks Smith, “Didn’t you ever want to own one?” The northerner demurs but the Colonel crows, “There’s nothing like it!” He makes Hero stand on a log and makes Smith guess how much he is worth – the play’s version of a slave auction.

After this, the Colonel parades around with his giant feather in his cap and then stops to declare exuberantly, “I am grateful every day that God made me be white!” This line got a laugh from the audience, but it was a slightly shocked and uncomfortable laugh because the line exposes the truth of white privilege, and the ways in which it is still unacknowledged in American culture.

When Boss Master staggers off to find his regiment, Hero and Smith have a discussion about emancipation and all that it promises. “There is more to freedom than I can explain,” the northerner says. There’s a revelation in this section of the play that I will not divulge in the event you will go to see it; but it too exposes the significance and power of misreadings within the slave system, and within Civil War culture.

In the End

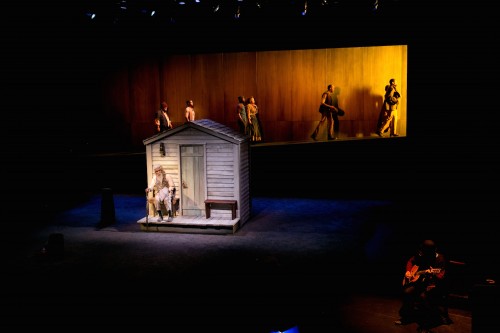

Father Comes Home does compelling work in its dramatization of slavery and the Civil War. Throughout, Parks manipulates the audience’s expectations of Hero. The audience assumes from his name and his role as the protagonist that he will embody the noble emancipation narrative. But from the beginning, Hero is no hero; most of the choices he makes self-serving and destructive of his relationships. At the end Part 3, he sits with his dog on the steps of a slave cabin, gathering the energy to bury the Colonel, whose body he has brought back to the plantation. “These are my hands now,” he says. But he is alone, and his future is uncertain. This last scene suggests that subsequent segments of Father Comes Home from the Wars will continue to complicate our beliefs about slavery and freedom, and the role of warfare in negotiating their terms.