By David Silkenat

Like many people, I was horrified by Trump’s call for a Muslim ban during the campaign and his Executive Order halting travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries. I was outraged that refugees escaping persecution and war were being denied sanctuary in the United States, especially after they had been through a long and detailed vetting program before being granted that privilege.

I have spent much of the past several years thinking and writing about the refugee experience. Although my research is specifically about refugees during the American Civil War and not those fleeing from Syria or Yemen, I have been struck by the commonalities of their experiences over space and time. Here’s what I wish the Trump Administration knew about refugees before implementing any kind of policy:

1. Ignoring a refugee crisis doesn’t make it disappear.

Among the Civil War’s earliest refugees were thousands of enslaved African Americans who fled to Union lines in 1861. Some Union officers initially refused them entry into military camps and believed that these fugitives would return to their plantations when they were turned away. But these refugees often would not – and could not – go back. Slave owners had amped up punishments for slaves who tried to run away and slave patrols were authorized, often for the first time, to use lethal force. In this sense, many modern refugees are not unlike slaves running away during the Civil War: facing violence at home, they braved a dangerous gauntlet in the hope of finding sanctuary. Denying refugees entry to the United States today doesn’t mean they can go home; in fact, sending refugees back to Syria, Iraq, or Yemen can be tantamount to a death sentence.

For this reason, they are likely to keep trying to gain entry. During the Civil War, black refugees continued to arrive in Union lines in large numbers, and their presence ultimately played a significant role in changing federal policy. Their presence compelled Union generals and the federal government to craft policies to deal with their health, safety, and job prospects, which culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation.

2. Refugee populations are much more diverse than most people think.

Fugitive slaves weren’t the only refugees in the Civil War. White Southerners were also driven from their homes during the fighting. Those who were sympathetic to the North fled towards Union lines while the majority sought sanctuary in the Confederate interior. Many of these refugees were quite wealthy, including Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s wife Varina and their children, who twice fled Richmond as refugees.

Today’s refugees demonstrate similar diversity. Some Syrian refugees are fleeing ISIS, others the Syrian government (and many both). Refugee camps tend to obscure enormous class and educational differences among refugees. You can find many highly educated people (doctors, lawyers, engineers) who have ended up in refugee camps. We need to acknowledge and value the diversity within the refugee population, recognizing that not all refugees have the same needs and experiences.

3. Extreme vetting doesn’t work and usually backfires.

When Southern white Unionists entered Federal lines, they were usually interrogated. Sometimes they were made to pledge their loyalty to the Union. Federal officials had good reason to be suspicious: Confederate spies often masqueraded as refugees. Yet, they also knew that making life too hard on white Unionist refugees would be counterproductive and that white refugees could be valuable assets. Consequentially, thousands of white refugees ended up fighting for the Union army. Today, Trump’s policy of “extreme vetting” prevents these kinds of opportunities. Rather than keeping out terrorists, extreme vetting is more likely to alienate potential allies.

4. Caring for refugees isn’t prohibitively expensive, and refugees usually end up contributing more than they receive from the federal government.

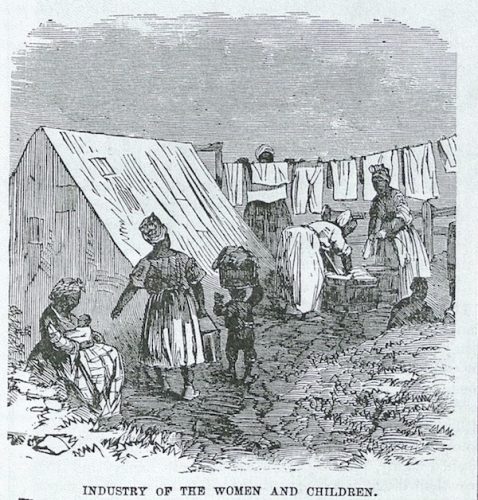

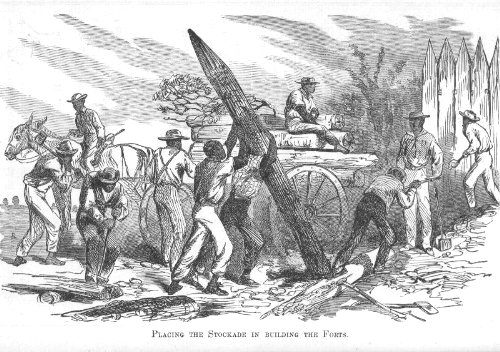

In 1864, Vincent Colyer, a refugee aid worker in North Carolina, wrote a book about working with black refugees entitled, Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army in North Carolina. The title here is key. Colyer argued that black refugees did much more to help the army than the army did to help refugees.

While the army may have provided rations, black refugees built fortifications, served as scouts and spies, and ultimately became soldiers. Refugees today are equally eager to go to work in the United States. Whether they are in refugee camps or resettled elsewhere, refugees are more likely to provide a boost than a drain on the economy.

5. Refugee crises don’t end when the fighting ends.

Although major conflict in the Civil War ended in April 1865, many refugees could not return home. To help freed people, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau (officially the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands) to assist those displaced (both white and black) by the war. One of the central political struggles early in Reconstruction centered on whether the work of Freedmen’s Bureau should continue after the war’s end. In overriding President Andrew Johnson’s veto, Congress correctly recognized that refugees of both races needed the support of the Federal government, even after the armies had disbanded. Refugees today need the same kind of support. Charities and religious organizations can do some of this work (as they did in the 1860s), but the Federal government is instrumental in providing some aid once refugees arrive and to help them in their transition to a new life.

***

Ultimately, during the Civil War era and today, what makes wartime civilian displacement into a refugee crisis is the unwillingness of the governments (local, national, and international) to help refugees. If history teaches us anything, it is that opening the door to refugees and providing a modicum of support can prevent an enormous amount of suffering, while simultaneously gaining allies and strengthening our moral standing in the world. While I doubt that Donald Trump will read either my book or this blog post, the Administration needs to recognize the long and complex history of the refugees in the United States, and encourage a thoughtful and welcoming policy.

David Silkenat teaches American history at the University of Edinburgh. He is the co-host of the Whiskey Rebellion Podcast and is donating the royalties from “Driven from War: North Carolina’s Civil War Refugee Crisis” to help refugees hurt by Trump’s travel ban.

1 thought on “The Resistance Files: 5 Things I Wish Donald Trump Knew About Refugees”