By Betsy Golden Kellem

Recent Trump administration characterizations of the news media as an “opposition party” have invited debate about the tension between liberty, security, and transparency. The President’s insistence that only sympathetic media outlets have the ability and the privilege to accurately represent his administration is shocking, and seems unprecedented in modern memory. Yet this is not the first time members of an American political party have attempted to quiet voices they’d rather not hear.

During the 1790s, the new United States was reckoning with France and Britain as the two major world powers – and these relationships were fragile at best. When America and England signed the Jay Treaty in 1795, the French were upset at what they perceived to be a pro-Britain bias and began angrily seizing American ships.

In 1797, President John Adams sent a delegation to France to negotiate smoother relations, and before they got to work, the three French envoys – who came to be known in diplomatic communications as X, Y and Z – asked for a $250,000 kickback from the U.S. delegation as a prerequisite to talking. Negotiations broke down and news of the “XYZ Affair” made it to the newspapers, setting public opinion on fire and quickly giving rise to the snappy nativist slogan, “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.”

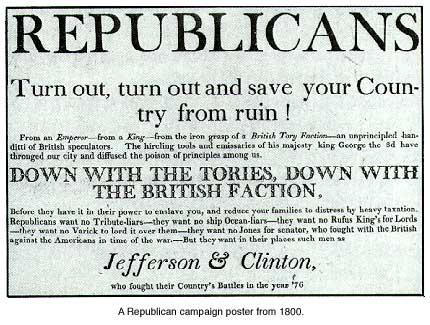

This was also a time of severely partisan strain between the nation’s first political parties: Federalists and the Republicans. In this diplomatic context, the Federalists thought the Republicans were too familiar with European liberalism while the Republicans believed the Federalists were closet monarchists.

In the wake of the XYZ Affair, broad anti-French sentiment empowered President John Adams and the Federalists to expand the American military and begin an undeclared “Quasi-War” with France. In addition, over the objection of a Republican minority, the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, a suite of four laws crafted to attack people and speech deemed antithetical to American government.

In the Sedition Act, Federalists drew upon the English common law tradition of seditious libel to criminalize “false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States.” Thus armed to silence Republican opponents, the Adams administration prosecuted more than two dozen individuals for speech critical of the U.S. government.

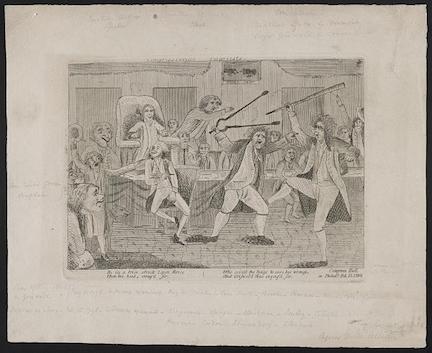

Matthew Lyon of Vermont was a Republican congressman indicted for libel under the Sedition Act in 1798 – not coincidentally, soon after he brawled on the House floor with Federalist Roger Griswold of Connecticut over an insult to his war record.

Federalists seized upon a letter of Lyon’s in which he criticized the Adams administration, claiming to see “every consideration of public welfare swallowed up in a continual grasp for power.”

Lyon stated at trial that he had no intent to undermine the government, and declared the Sedition Act unconstitutional. This did not stop the jury from sentencing him to four months in jail and a $1,000 fine; but it didn’t keep Lyon from re-election, either, making him the first American politician to be elected while in jail.

In November 1799, British-born lawyer and editor Thomas Cooper complained about government spending, claiming that before the Federalists came to power, “[o]ur credit was not yet reduced so low as to borrow money at eight per cent. in time of peace.” He further questioned the wisdom of building a standing army with borrowed money to fight an undeclared war (thereby very possibly provoking a real one). In response, the government declared him “a person of a wicked and turbulent disposition designing and intending to defame the President of the United States.”

The federal judge in Cooper’s case, Samuel Chase, urged jurors to consider Cooper’s crime in a broader, populist context: “One observation must strike you, viz.: That these charges are made not only against the president, but against yourselves who elect the house of representatives.” Chase also accused Cooper of being a paid protestor: “there is room to suspect that in cases of this kind, where one party is against the government, gentlemen who write for that party would be indemnified against any pecuniary loss.”

The jury instructions were chilling, and plain: “Licentiousness of the press,” Chase warned, “is the more slow, but most sure and certain, means of bringing about the destruction of the government.” A receptive jury sentenced Cooper to a $400 fine and six months’ jail time.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were zealously enforced but were also vociferously protested. The Annals of Congress in 1799 note “petitions and remonstrances from 1,487 inhabitants of the county of Franklin, in Pennsylvania, praying for the repeal of the alien and sedition laws.” With James Madison and Thomas Jefferson at the pen, Virginia and Kentucky drafted resolutions calling the laws unconstitutional and threatening non-enforcement. Censorship “ought to produce universal alarm,” Madison wrote, free speech being “the only effectual guardian of every other right.”

We would do well to remember that opposition to the overreach and vindictive politics of these laws was not in vain: resistance to them helped Thomas Jefferson defeat Adams in the contentious 1800 Presidential election, decided in the House of Representatives by contingent election. In a turn of events that he surely relished, Matthew Lyon cast Jefferson’s winning vote.

While Jefferson pardoned all convictions under the Sedition Act, the law’s expiration was not the end of the story. Fear of socialists, pacifists, foreigners, and communists successfully fueled federal anti-sedition legislation in 1918 and 1940. Not until the landmark New York Times Co. v. Sullivan case in 1964 did the Supreme Court state that attack on the Sedition Act “has carried the day in the court of history.”

If we are surprised to learn that American history so often shows the bruise of government censorship, we can be heartened that in each case, opposition ensured the fault did not become permanent.

Betsy Golden Kellem (@betsykellem) is a media lawyer and historian. She blogs regularly at Drinks With Dead People.

Featured Image credit: Betsy Kellem, “Justice,” Old State House in Hartford, CT.