By Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz

Last Tuesday Donald J. Trump gave his first address to a joint session of Congress. In it, he made repeated referrals to the impending 250th anniversary of the United States, which will take place nine years from now—assuming our democracy survives the current administration. After proclaiming that a “new chapter of American Greatness is now beginning,” Trump chose to look forward. Ever Trump, he could not help but declare, “It will be one of the great milestones in the history of the world.”

He went on to recount how, in 1876, “citizens from across our Nation came to Philadelphia to celebrate America’s centennial.” (Fact check: True. Historians estimate that 1 in 5 of the forty-six million inhabitants of the United States made the trip between May and November that year.) Trump described how, at the Centennial, American entrepreneurs highlighted innovation: Bell’s telephone, Remington’s typewriter, Edison’s telegraph. Calling these past inventions forth, Trump imagined a bright future for the nation just nine years from now, one based on new inventions and products of “the American spirit.”

Listening to the speech out of a mingled sense of duty and horror, I was startled by these mentions of the sestercentennial commemoration, and even more by his invocation of 1876. As I thought longer, though, it made perfect sense: Americans in 1876 also celebrated American technological ingenuity and used it as a sign of national progress, despite evidence to the contrary.

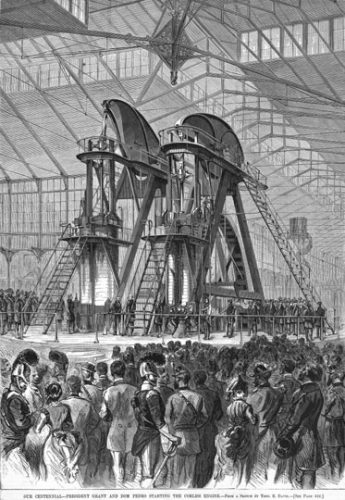

When President Grant declared the exhibition open on May 10, 1876, one thousand singers burst into the Hallelujah Chorus. Machinery Hall featured acres of machines surrounding a steam engine that rose forty feet above the ground.

Horticultural Hall displayed plant specimens, while Government Hall featured displays by government entities and the Smithsonian, which featured a Centennial Indian exhibit. Although an Agricultural Hall gave homage to America’s rural past (and present), what Americans celebrated in 1876 was modern technological innovation—presented as a shorthand for progress.

As historian Dee Brown has noted, “Because it was the Republic’s hundredth birthday, Americans were inclined to examine their past, to wonder about themselves and their institutions, and to seek an identity upon which to base their future.” And they did, imagining a future filled with wonder, progress, and innovation. After all, it was the great wonder of the nineteenth-century, the railroad, which brought so many to Philadelphia that summer.

But as in America today, where Trump’s predictions of greatness obscure the ways in which he is redefining “American” to omit immigrants and people of color, the 1876 celebrations glossed over a host of contradictions in American democratic life.

As they celebrated in Philadelphia, crowds learned of the Sioux defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn, reminding those who were willing to hear it that American expansion had been achieved at the expense of the American Indian population.

It was during the Centennial that presidential candidates Samuel J. Tilden and Rutherford B. Hayes campaigned in the build-up to an election that would effectively end federal Reconstruction (not to mention one in which the winner of the popular vote did not become president).

That summer in Philadelphia state exhibitions were banned from referencing the Civil War, beginning a fifty-year period of Lost Cause historical revisionism that ignored the promises of emancipation and promoted racial inequality.

During the Centennial exhibition, Women’s Day was held on election day (November 7) because women would be free while men (who clearly would have no interest in such a day) were busy at the polls.

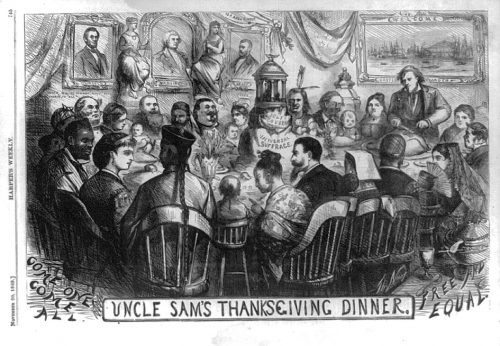

As in Trump’s America, these occlusions did not go unnoticed. Marginalized Americans insisted that they, too, deserved a place in the American story and a place at the American table.

During Centennial summer, Frederick Douglass spoke at the Republican Convention, reminding his audience that all of the promises of emancipation and enfranchisement meant nothing if African American men were “unable to exercise that freedom.” He added, “The question now is, Do you mean to make good to us the promises in your constitution?”

When he arrived for an official Centennial ceremony, Douglass was first denied entry by Philadelphia police. Ultimately he was allowed to sit on the main platform, but that was all this famous American orator was allowed to do. Decrying such marginalization, Howard-graduate and Reverend George Williams delivered an address in Washington, D.C., entitled a “Negro Declaration of Independence” that July 4. He declared, “we, the negro people, like all other Americans, will, in the second century of our independence, be assured of FULL AND EQUAL JUSTICE BEFORE THE LAW.”

That same July day, Susan B. Anthony issued a similar challenge on behalf of American women. She interrupted a ceremony in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall to scatter copies of a similar document, one proclaiming “our full equality with man in natural rights” and woman’s “absolute right to herself.” She later referred to this protest as her “Centennial growl.” Woman’s rights reformer Lucy Stone, too, urged a “moral protest” on the 4th.

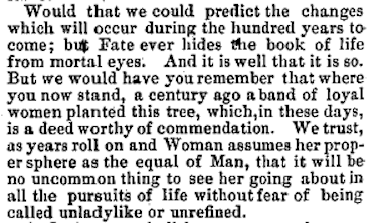

The year prior, Stone had published in her Woman’s Journal a letter from a group of New Hampshire women. Ostensibly written to the “Ladies of 1975,” they had predicted that, long before a hundred years from their writing, “Woman” would have assumed “her proper sphere as the equal of Man” and that it would be “no uncommon thing to see her going about in all the pursuits of life without fear of being called unladylike or unrefined.” Their hopes have proven far too optimistic.

As he campaigned in 2016, Trump famously promised to “Make America Great Again.” In last week’s speech, he added to this, vowing to bring us to “250 years of glorious freedom,” ignoring all for whom the past 250 years has not been universally marked by freedom. Throughout his campaign, he routinely cast aspersions upon Mexicans, Muslims, immigrants, and African Americans. His offenses to women, spoken and performed, are widely known.

Is it any coincidence that these same people were the ones obscured by celebrations of progress in 1876? As we move forward toward a new commemorative moment, and as Trump invokes a distorted version of the American past, we cannot afford for displays of American innovation and so-called progress to overshadow those who are intentionally sidelined, marginalized, discriminated against, or left out of the narrative of what—and who—makes America great. We need to meet Frederick Douglass’ challenge, to make good the promises of our constitution.

Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz is a nineteenth-century historian. Her book, The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism, was named a Kansas Notable Book in 2014. She is now working on a project about nineteenth-century women’s rights reformers and the intersections of their ideology about women’s rights and female citizenship with their experiences of motherhood. You can find her on Twitter @laughschultz.