Daniel Gorman Jr.

If there is an upside to the first two months of the Trump administration, it is the way that archivists, scientists, and journalists have fought this presidency’s anti-intellectual policies. In the past five months, groups of so-called “guerrilla archivists” downloaded federal climate data before it was deleted, ensuring that scientists can access research that the government’s new leaders do not wish to acknowledge (The Conversation reported on this topic in February.)

But the general public has not heard as much from historians on the administration’s censorship culture. Trump’s condemnation of the news, his comfort with “alternative facts,” his racist invective, and his administration’s pending cuts to academic research are enough to warrant concern.

Professional and amateur historians (and those interested in history in general) must be prepared to do battle against autocracy and willful ignorance in American life. Here are some strategies for keeping our work viable, secure, and uncensored.

Archiving Humanities Organizations’ Projects

The most pressing concern for historians is the potential defunding of the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. While many NEH-funded projects exist on university-owned web domains, the loss of NEH funding will at minimum impede ongoing archival processing and website maintenance. At worst, some of these NEH-funded projects and their websites will cease to exist. All those PBS documentaries, primary sources, timelines, etc.? Gone. Decades of NEA papers archived on the web? Gone. The potential loss of data from these three organizations would negatively affect students, scholars, and ordinary citizens who want to learn about history.

Just as scientists at Penn, Toronto, and UCLA downloaded climate data en masse, historians and archivists must archive NEA, NEH, and CPB web projects. Download e-books. Save HTML from webpages. Take screenshots. Make PDFs of digital projects, one webpage at a time. Store these files on external hard drives and cloud accounts (although hard drives are better, because they’re not connected to the web). Paper redundancies are great, but right now the priority should be saving the raw electronic data; printing can come later.

For sophisticated guerrilla archiving, historians can view the NEA, CPB, and NEH sites, page by page, and add the URLs to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, which saves archived copies of websites. As with anything on the Internet, we cannot assume the Wayback Machine will always be there, but for now the Machine is the best widely available way to archive born-digital sources.

These forms of archiving are not particularly hard to do — you can add links to Wayback or download PDFs in seconds — but it will take coordinated efforts and substantial server space to, say, archive all data from the Influenza Encyclopedia. Historians, archivists, and I.T. specialists must be willing to collaborate on this work, even if their institutions do not offer financial assistance.

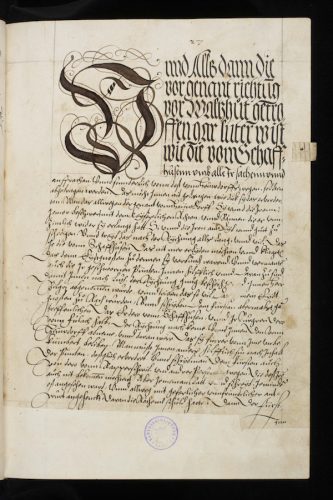

Archiving Primary Materials

Do you frequently consult primary sources from Project Gutenberg, HathiTrust, or Internet Archive? If so, save them to your hard drive, external drive, etc. Do not leave freely available resources online with the assumption they will always be there. Moreover, when you download resources relevant to your research specialty, preserve materials from and about diverse groups of people, so that you save a range of historical voices. Adeline Koh and Roopika Risam, among others, have championed the revision of Wikipedia to include women and people of color. Historians must similarly archive materials from a variety of viewpoints, so that no one group’s history is preserved at another’s expense.

Should the current (or a future) administration pursue censorship, it may be necessary to download text, audio, and visual materials currently under copyright. This poses the moral dilemma of violating copyright law. However, if we get to the point where the law is being used to limit what information Americans can consume, then by all means save what materials you can. You will be in good historical company — centuries of thinkers have hidden their work and protested publicly when their governments turned against free expression.

Storing Data

To save (and potentially hide) reams of information, we must be prepared to store them. Clear out your attic or external hard drive to make room for your localized archive. Moreover, save electronic files in formats viable for the long term.

For text documents, save plain ASCII (or, in Mac world, .txt) copies, which will retain words and characters, but not formatting.

Save images as TIFFs, which are larger but higher-quality files. JPEGs are fine when initially produced, but the quality will go down every time you crop or otherwise edit them.

There is more flexibility in terms of audio format — WAV, mp3, m4a, AAC — so long as the files are playable in more than one computer program. AAC files sold on the iTunes store before 2009 were locked, meaning they will only play on computers synced to one consumer’s email address. As with any act of archiving, the more copies you have of these files, the better.

Creating Your Own Records

Much the way medieval chroniclers dutifully recorded significant dates and events in long chronologies, we must keep logbooks of major political developments. As the Press Secretary and President of the United States deliberately spread misinformation, it is important for historians to read widely, save copies of news articles and publicly available sources, and keep a record of what is happening. This will make it easier to build arguments, whether in the news, in scholarly research, or in court, against the administration’s misbehavior.

Taking Precautions

At the risk of sounding like a member of the tinfoil hat brigade, we all should be careful when working electronically. Use encrypted messaging services like Signal, or operating systems such as Tor that hide your I.P. information. Keep the really sensitive stuff offline. We have to be in the business of guerrilla history for the long haul, and that means keeping our ideas and ourselves safe.

Further Reading

The Association of College & Research Libraries (ACLR) has an upcoming webinar on April 11 about good digital preservation techniques. For further reading on best archival practices, digital humanities, and representing the history of diverse audiences, I recommend the following readings (with a shout-out to my former digital history teacher, Deb Boyer, for introducing me to them):

- “The NINCH Guide to Good Practice in the Digital Representation and Management of Cultural Heritage Materials”

- Roy Rosenzweig and Daniel Cohen, Digital History (2005), Introduction – “Promises and Perils of Digital History,” Chapter 3 – “Becoming Digital,” Chapter 7 – “Owning the Past,” and Chapter 8 – “Preserving Digital History”;

- “Personal Archiving,” Digital Preservation, Library of Congress

- “Strategy for Digitizing Archival Materials for Public Access, 2015-2024,” Digitization at the National Archives, National Archives, December 2014.

- Dan Cohen, “Professors, Start Your Blogs,” DanCohen.org, August 21, 2006

- Robert B. Townsend, “How is New Media Reshaping the Work of Historians,” Perspectives on History, November 2010

- Trevor Owens, “Crowdsourcing Cultural Heritage: The Objectives are Upside Down,” Trevor Owens, March 10, 2012

- Adeline Koh and Roopika Risam, “The Rewriting Wikipedia Project,” Postcolonial Digital Humanities, via Koh’s website.

Daniel Gorman Jr. is a history Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rochester, where he researches nineteenth-century American religion and culture. He received his M.A. from Villanova University and is a member of Phi Beta Kappa. You can read Dan’s work at rochester.academia.edu/DanielGormanJr and https://tangentsusa.wordpress.com/, and follow him on Twitter (@DanGorman2).